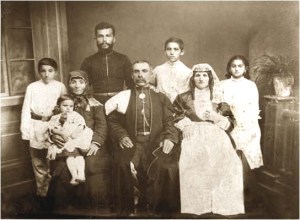

(Photograph: P. Papalov’s photographic studio:http://www.photomuseum.org.ge/photographers/papalov/papalov_en.htm)

The year was 1946, and Diaspora Armenians from the Middle East were invited to repatriate Soviet Armenia.

My father was around 22 years of age, and he owned a building in Burj Hammoud, the Beirut suburb that was founded by the survivors of the 1915 Armenian Genocide. He did not live in Burj Hammoud but visited once every few months to collect rent from tenants. He was living in Niha, al-Chouf, his hometown, and the trip back then consumed an entire day given the nature of the roads and unavailability of affordable methods of transportation.

One day, my father arrived in Burj Hammoud and went to visit his friend Jean.

Jean was the son of genocide survivors who came to Lebanon to escape the atrocities of the Turks and secure a safe future for their children in a hosting country. The Armenians became an essential component of this country’s fabric: They got naturalized and contributed to the country at the political, economic, social, and cultural levels.

Jean related to my father the family’s desire to leave Lebanon for good and return to Armenia. Armenians, by the thousands, were preparing to leave, and his entire family wanted to go back: grandparents, uncles, aunts, sisters, brothers, nieces, nephews, and their respective families. As everyone was preparing to leave, property prices dropped, and Jean offered my father several houses for the price of one.

My father showed skepticism: “What if conditions back home are difficult? How will you work? You will have to start from nothing, do you realize that?”

Jean: “Yes I do, Saiid, but it is worth it. There is nothing like home. We want to go back to our home country.”

My father was outraged: “But this is your home! You, your sisters, brothers, and cousins were all born here; you own land and you have your own business; you are Lebanese Armenian.”

Jean: “No Saiid. There is no place like home. My father wants to go back. We owe it to our country.”

Saiid: “This is your country Jean! You have Armenian schools, churches, newspapers, radio stations, and restaurants right here; you have a little Armenia in Lebanon. Why do you want to leave?”

Jean: “You will never understand, will you? The longing to go back home is greater than anything else. We want to go back to our roots. If one loses his land, one loses his heritage.”

My father shook his head: “What if the conditions in Soviet Armenia are bad? Are you willing to risk everything and see your children starve?”

Jean: “My brother is going there next week. This will give us a head-start. We are artisans after all, and we can work anywhere.”

Saiid: “Why don’t you ask your brother to write back and tell you about the situation?”

Jean: “Oh no! No one is allowed to do that. The censorship is great! This is Soviet Armenia, and that would be considered treason!”

Though Armenia became briefly independent in 1917, it fell under the Soviet rule until 1991. Heavily exercised censorship prevented Armenians from relating any information about the situation in Armenia to Armenians abroad. The soviets insisted on painting a beautiful image about Armenia to encourage repatriation, but they didn’t hesitate to exile returning Armenians to Siberia.

My father said: “Jean, are you telling me that you will sell everything and move to a place you do not know in what condition it is? Are you willing to risk your life and the life of your children to go back to your homeland?”

Jean: “Saiid. It took Odysseus ten years to make it back home but he wasn’t deterred. Nothing could lure him from returning home. No land; no amount of money; no woman.”

Saiid: “Odysseus had a home and a wife to go back to. It is not like he was going back to nothing.”

After a short pause, my father continued: “If your brother cannot write back and tell you about the situation back there, why doesn’t he send a message in some other form?”

Jean laughed: “You and your creative mind! Are you going to think up a secret way of communication?”

My father responded in all seriousness: “Yes. I am going to.”

After a longer pause, my father said: “Since you say your brother might risk his life if he relates any news to you about Armenia, you should think twice about going back. This alone is a sign that something is wrong. He doesn’t have to report things in writing. Have him instead send you a photograph of him.”

Jean: “Of him?”

Saiid: “Yes, of him. If the situation is excellent, he should send you a picture of him standing up. If the situation is mediocre, he should send a picture of him sitting down. If the situation is bad, he should send a picture of him squatting. This way, you will know what you’re getting yourself into.”

Jean liked the idea. It was smart, and it did not put the life of his brother at risk.

Four months passed before my father could make it back to Burj Hammoud for a day.

As he walked down Arax, the main street, he saw Jean running toward him.

“Saiid! Saiid!” Jean yelled.

“How are you doing my friend?” asked my father.

“Come with me,” Jean panted.

“Where to?”

“Just come. I need to show you something very important.”

“Did you hear from your brother?”

“Don’t ask questions. Just come.”

“Tell me! What is going on?”

“I will not say a word. Come. Hurry up!”

My father complied and had to run to keep up with Jean. After 10 minutes of running through the streets of Burj Hammoud, they reached Jean’s house, climbed up the stairs to the third floor, and let themselves into the apartment before Jean locked the door behind him. He led my father to the bedroom, reached for a key on top of the closet and opened it up. He brought out a small tin box, reached for a small key hidden in his shoe, and opened up the box. He took a photograph out and handed it to my father.

My father sat on the edge of the bed and looked at the photograph. It was a photograph of Jean’s brother in Armenia. He wasn’t standing up, he wasn’t sitting down, and he wasn’t squatting. He was spread face down on the floor.

My father was dumbstruck. He looked up at Jean and saw tears in his eyes. My father sighed and shook his head.

“We would have sold everything and gone there had it not been for this photograph,” Jean cried, “we could have lost everything.”

“Did you tell anyone?” my father asked.

“No. Just immediate family,” replied Jean.

“You should. You should help people by telling them.”

“I am afraid someone would hurt us.”

“You are safe here. Your brother can come back claiming the need to pick up his family.”

Jean nodded.

“I guess I have to,” he said.

The two friends hugged.

Jean did just that. He told his neighbors and friends, and he told strangers on the streets. In short, he told anyone who would listen. Word spread that Armenia is probably lost forever, and the Lebanese Armenians stayed in Lebanon.

I listened to this story dozens of times, but it was not until my father passed away in 2010 at the age of 85 that I realized that the Armenians still talk about it. It has become another story of survival and a part of the Lebanese Armenian heritage.

We always have a choice in life, but sometimes we heed the call of heart more oftentimes than we ought to. I understand one’s love for one’s land; however, I have come to understand that home is not always where the heart is. Home is, most times, where we are safest.

Thanks Abir for sharing this

As Charlie Sheen says, this article is “WGNNINI!”

Pingback: A Story About The Armenian Diaspora in Lebanon | Blog Baladi